Suggested reading: On linearity

It is often easier to understand a concept if it can be connected to some other familiar concept. Like most electrical engineers, I was introduced to Linear Time-Invariant systems/filters in the framework of analyzing electrical signals and circuits. I recently took a class on linear dynamical systems which generalizes the notion of LTI systems using state-space. In this set of notes, I want to make the connection between LTI systems and Linear Dynamical Systems (LDS). I will focus on only discrete-time systems.

LTI System background Link to heading

Difference equation Link to heading

Given a sequence of numbers i.e a signal $u[n]$ indexed by $n$, we can define a system as an operation that produces an output $y[n]$ for every index $n$. If the relation between $y[n]$ and $u[n]$ is linear (weighted sum of $u[n]$ for different values of $n$) and that relation does not change with time, then we have an LTI system. For example, $y[n] = b_0u[n] +b_1x[n-1]$ is an LTI system that at each time step $n$ produces as output a weighted sum of the current value of the signal and the previous value of the signal $x[n-1]$. $b_0$ and $b_1$ are held constant making the system time-invariant.

Such a description of an LTI system is called a difference equation. The general form is

$$y[n] = b_0u[n]+b_1u[n-1]+…+b_ku[n-k] + a_1y[n-1] +a_2y[n-2] +…+a_p[n-p]$$

In this description, the output $y[n]$ is restricted to be causal: it only depends on past inputs and past outputs. We will limit our discussion to causal systems which all physical systems are.

Impulse response Link to heading

An impulse is a signal $\delta[n]$ that is $1$ at $n=0$ and $0$ elsewhere. For systems whose output only depends on the inputs $u[n]$ and not on past outputs, the coefficients or weighting factors $b_i$ are the response to an impulse. To see this, simply plug-in the impulse signal into the difference equation. Therefore, $h[n] = b_n$ is called the impulse response. Why is this useful? We can describe the LTI system using the convolution operation $\circledast$.

$$y[n] = h[n] \circledast u[n] = \sum_{k=-\infty}^{+\infty}u[k]h[n-k]$$

This equation can be understood visually as:

(1) flip the impulse response across the n=0 axis (y-axis) i.e $h[{-k}]$

(2) slide $h[{-k}]$ n times to the right effectively centering it at the value of n we are trying to compute the output for

(3) perform the summation for different values of $k$.

If you are having a hard to time visualizing, you can also just compare this convolution equation to the equivalent difference equation: set the impulse response to be the coefficients of the current and past input samples.

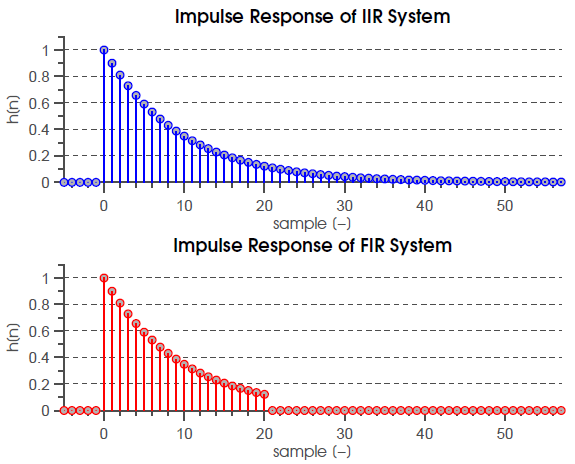

What about systems that depend on past outputs (systems with feedback)? It turns out that the impulse response for systems with feedback is infinitely long. Such systems are best described using difference equations or the frequency domain (next section).

Thus, we can characterize an LTI system using the impulse response and convolution operation. It’s pretty cool to think about the fact that you can understand the full behavior of an LTI system simply by stimulating it with an impulse. For example, a common application is in characterizing the acoustics of a room. We can model the room as an LTI system i.e something that scales and delays signals coming from a sound source and into a microphone; then we can play a loud impulse sound out of a speaker that lasts a short duration and record the impulse response with a microphone. Using the impulse response characterization of the room, we can now construct an inverse filter (an impulse response that when convolved with the room impulse response results in value of $1$) that counters the effects of the room.

Transfer function Link to heading

So far we have seen descriptions of LTI systems that are in the time-domain i.e we are looking at the signals as sequences. Is there another way to analyze the system? Maybe polynomials..

It turns out that the convolution of two sequences is just like multiplying two polynomials.

$$h[n] = b_0, b_1…b_n \hspace{1cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{1cm} H[x] = b_0 + b_1x + b_2x^2+…+b_nx^n$$

$$u[n] = u_0, u_1…u_n \hspace{1cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{1cm} U[x] = u_0 + u_1x + u_2x^2+…+u_nx^n$$

$$h[n] \circledast x[n] \hspace{1cm} \Leftrightarrow \hspace{1cm} H[x] * U[x]$$

Try multiplying out the two polynomials to see the equivalence to convolution. The transformation to go from the time sequence $h[n]$ to to the polynomial $H[x]$ is called the z-transform:

$$X(z)={\mathcal {Z}}{x[n]}=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }x[n]z^{-n}$$

$z$ in the equation is any complex number. Notice that the variable in the polynomial is $z^{-1}$ . You can interpret the power of the variable as a delay in the time domain i.e $x[n-k] = x[n]z^{-k}$.

For a finite impulse response (FIR), we have

$$h[n] = b_0, b_1…b_n \hspace{1cm} H(z) = {\mathcal {Z}}{h[n]} = b_0 + b_1z + b_2z^{-2}+…+b_nz^{-n}$$

The z-transform of the impulse response is called the transfer function. Why? Because it relates the input and output of the LTI system via a simple multiplication: $Y(z) = H(z)X(z)$. It answers how much and what parts of X(z) get transferred to the output.

For systems with feedback that have infinitely long impulse responses (IIR), we turn back to the general difference equation:

$$y[n] = b_0u[n]+b_1x[n-1]+…+b_x[n-k] + a_1y[n-1] +a_2y[n-2] +…+a_p[n-p]$$

Take the z-transform of all the terms:

$$Y(z) = b_0U(z)+b_1U(z)z^{-1}+…+b_kU(z)z^{-k} + a_1Y(z)z^{-1} +a_2Y(z)z^{-2} +…+a_pY(z)z^{-p}$$

$$H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{U(z)} = \frac{b_0+b_1z^{-1}+…+b_kz^{-k}}{1 + a_1z^{-1} +a_2z^{-2} +…+a_pz^{-p}}$$

The z-transform is a generalization of the Fourier transform. If you plugin $z = e^{j\omega}$ into the polynomial, you end up with the Fourier transform. It gives you a frequency ($\omega$) domain picture of what your system is doing. Let’s say you want to remove a certain set of sinusoids with really low frequencies like airplane takeoff audio noise in your vacation video recordings, you can construct an LTI system with a high-pass characteristic that lets only high frequencies pass and suppresses any low frequency sounds.

It is also helpful to decompose those polynomials in the numerator and denominator further into their roots.

$$H(z) = \frac{(z-p_0)(z-p_1)…(z-p_m)} {(z-q_0)(z-q_1)…(z-q_m)}$$

The roots of the numerator polynomial are called zeros because the transfer function is zero for those values. The roots of the denominator polynomial are called poles because the transfer function is infinitely large at those values of $z$. For example, we can model the human vocal tract (mouth, lips) as an LTI system whose inputs are signals from the larynx/voice box. We can model it as having only poles; often times the vocal tract simply lets through only a handful of frequencies called resonance frequencies. A pair of complex-valued poles can describe a single resonance.

A point here that confused me with poles is why we don’t ever see an infinitely large output if we can produce an input signal with the pole frequency and magnitude. The reason is that the z-transform for a causal system is only defined for regions of the complex plane outside a circle encircling the poles (see figure below). In other words, the transfer function in the frequency domain is only valid for signals in the region of convergence of the z-transform.

In this quick crash course on signals and systems, we looked at both time-domain and frequency-domain characterizations of LTI systems. How do these concepts relate to Linear Dynamical Systems?

Linear Dynamical Systems (LDS) Link to heading

Abstractly, a dynamical system models how a point in a geometrical space evolves over time. The point is also called the state. In a discrete-time linear system, the state can be defined as a vector $x(k)$ and its evolution by the following equation:

$$x(k+1) = Ax(k) + Bu(k)$$

Matrix $A$ describes the dynamics of how the state vector evolves over time. $B$ is the input matrix that describes how to absorb the information in the current input into the state.

We add another layer to the state-space: the output $y(k)$. The output of an LDS is computed as a function of the current state and the current input.

$$y(k) = Cx(k) + Du(k)$$

$C$ is the output matrix explaining the relation between the current state of the system and the output. $D$ is called the feedthrough matrix.

Thus an LDS is described with these two state-equations:

$$x(k+1) = Ax(k) + Bu(k)$$

$$y(k) = Cx(k) + Du(k)$$

In our description of LTI systems, we are constrained to single-input single-output (SISO) systems. With LDS, the description allows us to work with multi-dimensional inputs and outputs (MIMO). For example, if our system is processing videos, each frame of video could be an input vector $u(k)$ at time $k$.

LTI and LDS connection Link to heading

First, let us derive an FIR LTI system as an LDS system. FIR filter output is a weighted sum of the current input and the past inputs given by the difference equation:

$$y[n] = b_0u[n]+b_1u[n-1]+…+b_ku[n-k]$$

The “state” of an FIR system is its memory– it is a vector that stores the last $N$ input samples where $N$ is the memory size/filter length/impulse reponse length. If you implement the above equation in a programming language like C, you would use a FIFO queue to maintain the state of the system. Think of the equation below as just that– at every timestep, pop the last Nth value from the queue and push the current value on top.

$$x(k) = \begin{bmatrix} u[k-1] \\ u[k-2] \\ \vdots \\ u[k-N] \end{bmatrix}$$

The LDS state evolution equation is:

$$x(k+1) = Ax(k) + Bu(k)$$

$$ A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & & \cdots \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & \cdots \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} $$

$$ B = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \vdots \\ \end{bmatrix} $$

The dynamics matrix $A$ is simply shifting the elements in the state vector downwards by 1 like a FIFO queue and making room to absorb the current input $u[k]$. $B$ is selecting the input.

The output is simply:

$$y(k) = Cx(k) + Du(k)$$

$$ C = \begin{bmatrix} b_1 \\ b_2 \\ \vdots \\ b_n \end{bmatrix} $$

$$ D = b_0 $$

For IIR systems, the general difference equation, as before, is given by:

$$y[n] = b_0u[n]+b_1x[n-1]+…+b_x[n-k] + a_1y[n-1] +a_2y[n-2] +…+a_p[n-p]$$

The transfer function is:

$$H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{U(z)} = \frac{b_0+b_1z^{-1}+…+b_kz^{-k}}{1 + a_1z^{-1} +a_2z^{-2} +…+a_kz^{-k}}$$

To convert this to the state-space representation we can split the transfer function into a cascade as follows:

$$H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{U(z)} = (b_0+b_1z^{-1}+…+b_kz^{-k}) (\frac{1}{1 + a_1z^{-1} +a_2z^{-2} +…+a_kz^{-k}})$$

We can make the second term of the product the state of the LDS. The state vector will then effectively keep memory of the past outputs and inputs.

$$X(z) = (\frac{1}{1 + a_1z^{-1} +a_2z^{-2} +…+a_kz^{-k}})U(z)$$

$$Y(z) = (b_0+b_1z^{-1}+…+b_kz^{-k})X(z)$$

If we turn the transfer function back to time-domain form, we can see the dynamics matrix pop out:

$$x[n] = u[n] - a_1x[n-1] - a_2x[n-2] \dots -a_kx[n-k]$$

In vector form,

$$x(k+1) = Ax(k) + Bu(k)$$

$$ A = \begin{bmatrix} -a_1 & -a_2 & \cdots & -a_{N-1} & -a_N \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & \cdots \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $$

$$ B = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \vdots \\ \end{bmatrix} $$

To derive the output from the state vector and the current input, we first want to factorize out the $b_0$ term in the transfer function since that’s our feedthrough, $D$ matrix.

$$H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{U(z)} = \frac{b_0+b_1z^{-1}+…+b_kz^{-k}}{1 + a_1z^{-1} +a_2z^{-2} +…+a_kz^{-k}}$$

$$H(z) = \frac{Y(z)}{U(z)} = b_0 + \frac{(b_1-b_0a_1)z^{-1}+(b_2-b_0a_2)z^{-2} + …+(b_k-b_0a_k)z^{-k}}{1 + a_1z^{-1} +a_2z^{-2} +…+a_kz^{-k}}$$

Now,

$$y(k) = Cx(k) + Du(k)$$

$$ C = \begin{bmatrix} (b_1-b_0a_1) \\ (b_2-b_0a_2) \\ \vdots \\ (b_n-b_0a_n) \end{bmatrix} $$

$$ D = b_0 $$

Thus, we have state-space representations of our SISO LTI system fully described by the four matrices, A (dynamics matrix), B (input matrix), C (output matrix) and D (feedthrough matrix). These representations are not unique, we can perform a change of basis transform to get other representations encoding the same information.

What can we do with this new description? Besides the previously mentioned advantage of being able to work with multi-dimensional signals (MIMO), with SISO too, we can quickly learn about the properties of our system.

The LDS transfer function Link to heading

Let’s derive the transfer function in terms of the LDS parameters, $A, B, C, D$.

The z-transform of a time advanced signal is:

$$X(z) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} x(k+1)z^{-k} \\ = z\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x(k)z^{-k} \\ = zX(z)-zx(0)$$

Our LDS state-space equations are,

$$x(k+1) = Ax(k) + Bu(k), \hspace{1cm} y(k) = Cx(k) + Du(k)$$

Taking the z-transform on both sides,

$$zX(z) - zx(0) = AX(z) + BU(z), \hspace{1cm} Y(z) = CX(z) + DU(z)$$

Solving for X(z),

$$ X(z) = (zI-A)^{-1}zx(0) + (zI-A)^{-1}BU(z)$$

Substituting in the equation for Y(z),

$$ Y(z) = C(zI-A)^{-1}zx(0)+ H(z)U(z) $$

where $$H(z) = C(zI-A)^{-1}B + D$$

When the initial state $x(0)$ is $0$, $H(z) = Y(z)/U(z)$.

When we evaluate the above equation with the matrices we derived in the previous section, we get back our SISO form of the transfer function.

Poles are modes of the dynamics matrix Link to heading

The dynamics matrix $A$ captures how the state vector evolves over time. When there is no input $u(k)$ to the system and only an initial state vector $x(0)$, then the state vector at any time $k$ is given by $x(k) = A^kx(0)$. This is called the free state response. The free output response is $y(k) = CA^kx(0)$.

For certain vectors, $A$ will only scale it and not change its direction. Those vectors are eigenvectors ($v$) and the amount of scaling is the eigenvalue ($\lambda$). $Av=\lambda v$. To compute the eigenvalues, we find the roots of the characteristic equation $\chi(s) = det(sI-A)$. For the $A$ we derived for the SISO LDS case, $\chi(s) = s^n + a_1s^{n-1} + a_2s^{n-2} …$ Notice that this is the denominator of our transfer function. The roots of the characteristic equation which are also called eigenvalues are just the poles of the system.

In the transfer function section of the LTI background, we observed how the poles are complex z-values where the system output is essentially infinite although the transfer function is really only defined for the region of convergence (ROC): complex z-values that do not include the pole. The free state response is characterized completely by the eigenvalues of the dynamics matrix or the poles of the transfer function. In the LDS context, if we initialize a state to an eigenvector and have no input $u(k)=0$, then the state vector evolves by itself according to $x(k) = A^kx(0) = \lambda^k v$. $\lambda^k v$ is called a mode. There are as many modes as there are eigenvectors in the dynamics matrix.

To guarantee stability for any initial state vector $x(0)$, the modes have to decay to zero. This is possible only if the magnitude of all eigenvalues is less than 1. $|\lambda_i| < 1$

In the FIR case, where we have no poles, the eigenvalues of the dynamics matrix are 0. As we observed before the dynamics is simply that of a FIFO buffer. The mode decays within a finite-time (the length of the buffer). FIR systems are thus always stable. In the IIR case, the modes only tend to decay to 0 as time goes to infinity.

Other properties & Conclusion Link to heading

The state-space representation allows us to answer questions such as:

- Is there an input that could take the state of our system from an initial point $x(k_i)$ to some final point $x(k_f)$? How do we design an efficient input that could solve the problem? Wikipedia article on controllability

- Given input and output pairs can we observe the state? Wikipedia article on observability

The state-space representation offers a richer description of LTI systems. It enables working with MIMO signals and allows us to glean other useful behaviors of the system like stability, controllability and, observability.